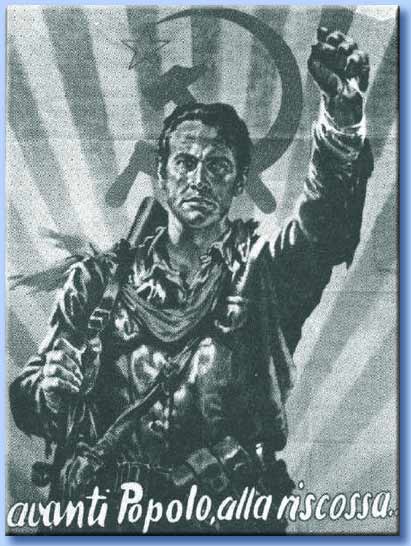

They were communists. The partisans, the local people who resisted the crushing, grinding cruelty of the fascist regime and it's economic system. Poor people. People of the land. Proud, clever, honest, family, community people. They are still here. They are in every handmade brick, olive tree, terraced hillside, vineyard and crumbling ruin. They are in every bottle of wine, every loaf of bread.

When we first visited the bar in Moiano, we stood on a large outdoor terrace paved with broken flagstone. In the mosaic of the paving spread a huge hammer and sickle. When clearing out an old partition wall in the house, I found the hammer and sickle stamped into the old bricks; and when removing old plaster from the wall outside what was once the front door, I unveiled a painted hammer and sickle. The proud symbol of the local resistance.

| abandoned transit station at top of the ridge with 'modern' campaign sticker |

In a Santa Fe bookstore, Bob found a book entitled An Umbrian War by Romana Petri, a translation of her Alle Case Venie published in 1997. Romana describes the fall of the fascists in Citta della Pieve through the eyes of a fictitious young orphan and her younger brother. It's told in thoughtful, ephemeral, occasionally confusing style with Alicina having conversations with her father's ghost, coping with treacherous nazi sympathizers, sending her younger brother on spy missions and finally abandoning her old family home and joining the rebel band in the mountains. Hearing the story set in the countryside right around our house thrilled me and inspired me to seek out and follow the the path of the partisans. Any excuse, really, to get up on the high ground and have a look around will do; but the idea of a history lesson as well as a mountain bike adventure turned the idea into a compulsion.

So Bob arrives. We scramble into the attic and dust off his bike, dig out his helmet and shoes, and have a good hard look at what the girls will ride. We're going to need water, of course, and the promise of a summit picnic as well as ice cream at the end. We'll have no map, but I've been studying the contours with Google Maps for so long, I've got most of it memorized. It'll be a little tricky since it's a point to point ride with the start in Citta della Pieve, about a half an hour away from our house. The girls have actually been to the summit of Monte Pausillo on school outings, so they know the way down from the top to Paciano. I'll have to drive us up to Citta della Pieve, guide everybody across the traverse and then return to the car, leaving Bob to accompany the girls down to Paciano and home.

| Monti Cetona e Amiata for anyone who might care |

I watched Thomasina and Zoe walk down from the turn-around thinking it wonderful we wouldn't have any foolish casualties. A little further on, Thomasina got the hang of it and off she went, just to skid and jump off in front of Isolde on the last pitch to the car. Jeesh! We've got some learning to do.